🇺🇸 English

Building a Polymarket Bot, Part 4

Dec 24, 2025

📒 Docs · ☎️ Telegram · 𝕏 @ZEITFinance · 𝕏 @autonomous_af

← Previous: Part 3, The Local Mirror

ZEIT FINANCE · Building a Polymarket Bot

Part 4 — Getting Filled

Introduction

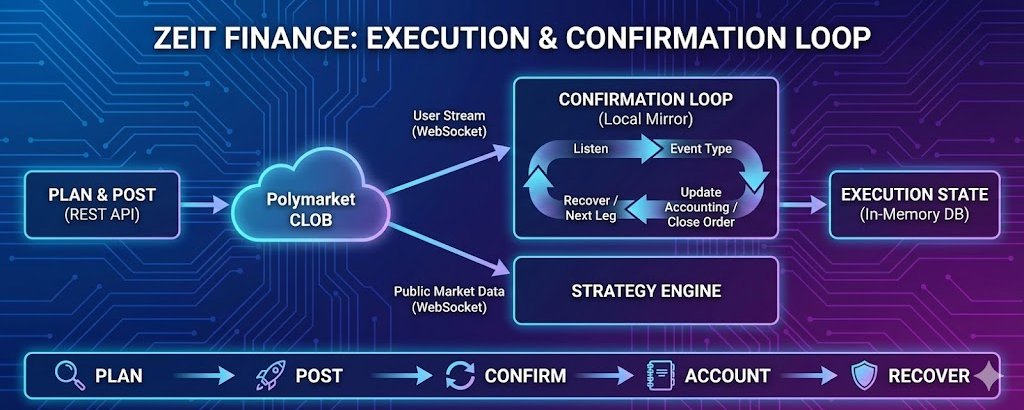

In Part 3, we built the Local Mirror to accurately see the market. Now, we must act on it.

Posting orders is easy—knowing what actually filled is the real work.

If you have ever automated trades on Polymarket, you have likely encountered the "phantom fill" scenario:

- Your bot places a market order, assumes the position exists, and moves on to hedge the next leg.

- Milliseconds later, you realize the fill was partial, delayed, or killed entirely.

Suddenly, your theoretically neutral strategy is carrying naked exposure. This is not an edge case, it is the default reality of trading on a CLOB.

The fix is to stop treating execution as a "fire-and-forget" action and treat it as a strict Confirmation Loop:

- Plan

- Post

- Confirm

- Account

- Recover

- Repeat 1.

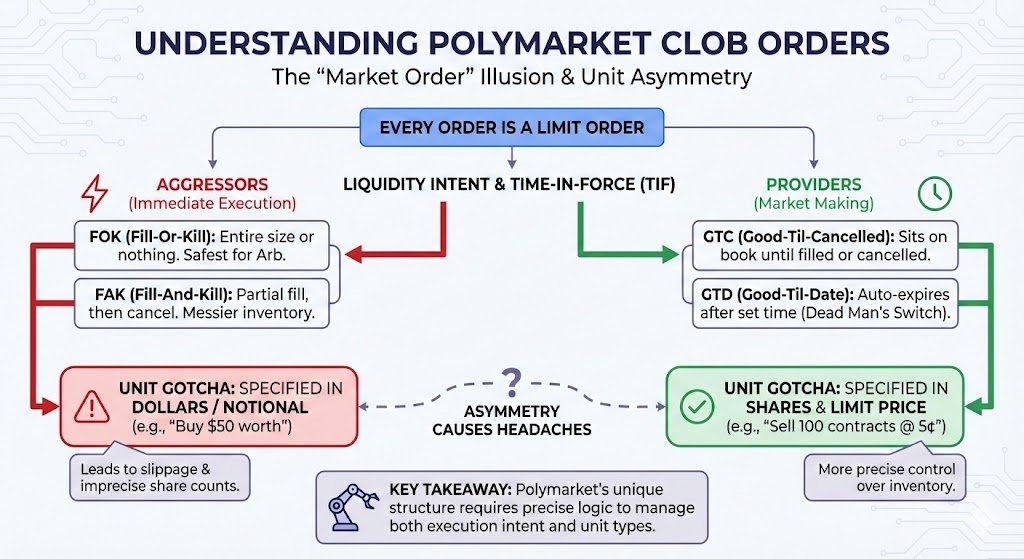

1. Know Your Tools: The "Market Order" Illusion

Before you write your execution logic, you need to unlearn a standard concept: Polymarket's CLOB doesn't actually have a "Market Order" packet.

Every order sent to the exchange is fundamentally a Limit Order. When you want to execute immediately, you are simply sending an aggressive Limit Order paired with a specific Time-In-Force (TIF) instruction.

Every order is fundamentally a Limit Order with different Time-In-Force instructions

Aggressive vs. Passive Intent

Categorize your orders by their liquidity intent:

The Aggressors (FOK & FAK)

Use Fill-Or-Kill (FOK) for immediate execution.

FOK is binary. It fills your entire size immediately or cancels the whole order. This is safest for arbitrage. It prevents you from getting stuck with half a hedge.

Fill-And-Kill (FAK) fills what it can and cancels the rest. This leaves you with partial inventory to manage.

The Providers (GTC & GTD)

Market makers rely on Good-Til-Cancelled (GTC).

Sophisticated bots prefer Good-Til-Date (GTD). This auto-expires the order after a set time (e.g., 60s). It acts as a dead man's switch. If your bot crashes, orders vanish instead of sitting as stale targets.

The "Dollar vs Share" Gotcha

One design choice breaks most new bots. Polymarket handles units differently depending on the trade type.

- Limit Orders: Specified in Shares and Price. (Sell 100 contracts @ 5¢)

- Market Orders: Specified in Dollars. (Buy $50 worth)

- FOK/FAK: Specified in Dollars with Min/Max shares.

This asymmetry complicates arbitrage logic.

You calculate an edge based on exactly 100 shares. The API forces a dollar input. Price slippage guarantees you end up with 99.8 or 100.2 shares.

You never get exactly 100.

⚠️ Critical Rule: Market orders are dollar-denominated. Always account for floating-point imprecision. Never assume exact share counts.

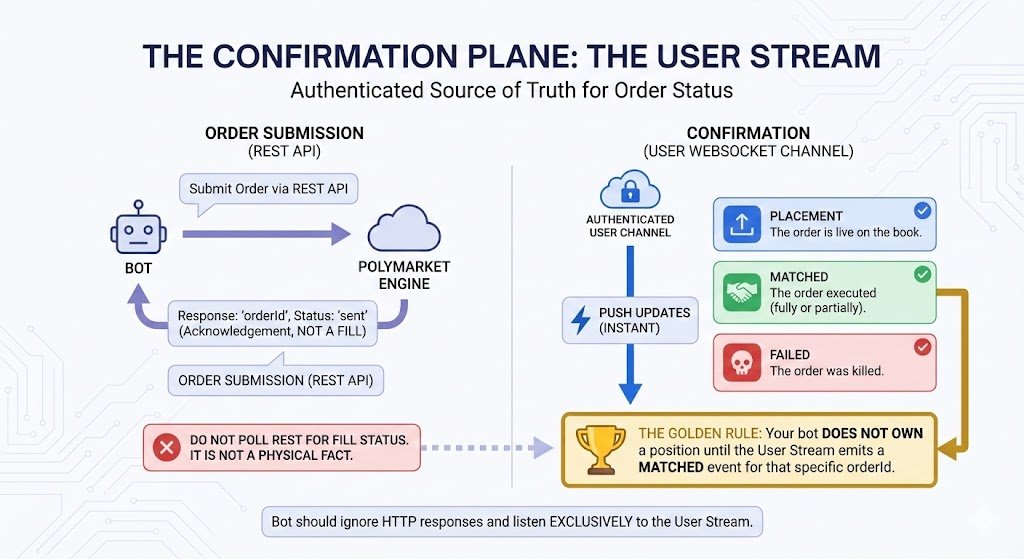

2. The Confirmation Plane: The User Stream

When you submit an order via the REST API, the response gives you an orderId and a status of sent. This is not a fill. It is merely an acknowledgement that the engine received your request.

"Filled" is a physical fact derived from the matching engine, and you should never guess at it by polling the REST API. You need the User WebSocket Channel.

While the Market Channel gives you public data, the User Channel is your authenticated source of truth. It pushes updates the instant your order state changes. Your bot should essentially ignore its own HTTP responses and listen exclusively for:

- PLACEMENT: The order is live on the book.

- MATCHED: The order executed (fully or partially).

- FAILED: The order was killed.

The User Stream is your only source of truth for order fills

💡 The Golden Rule: Your bot does not own a position until the User Stream emits a MATCHED event for that specific orderId.

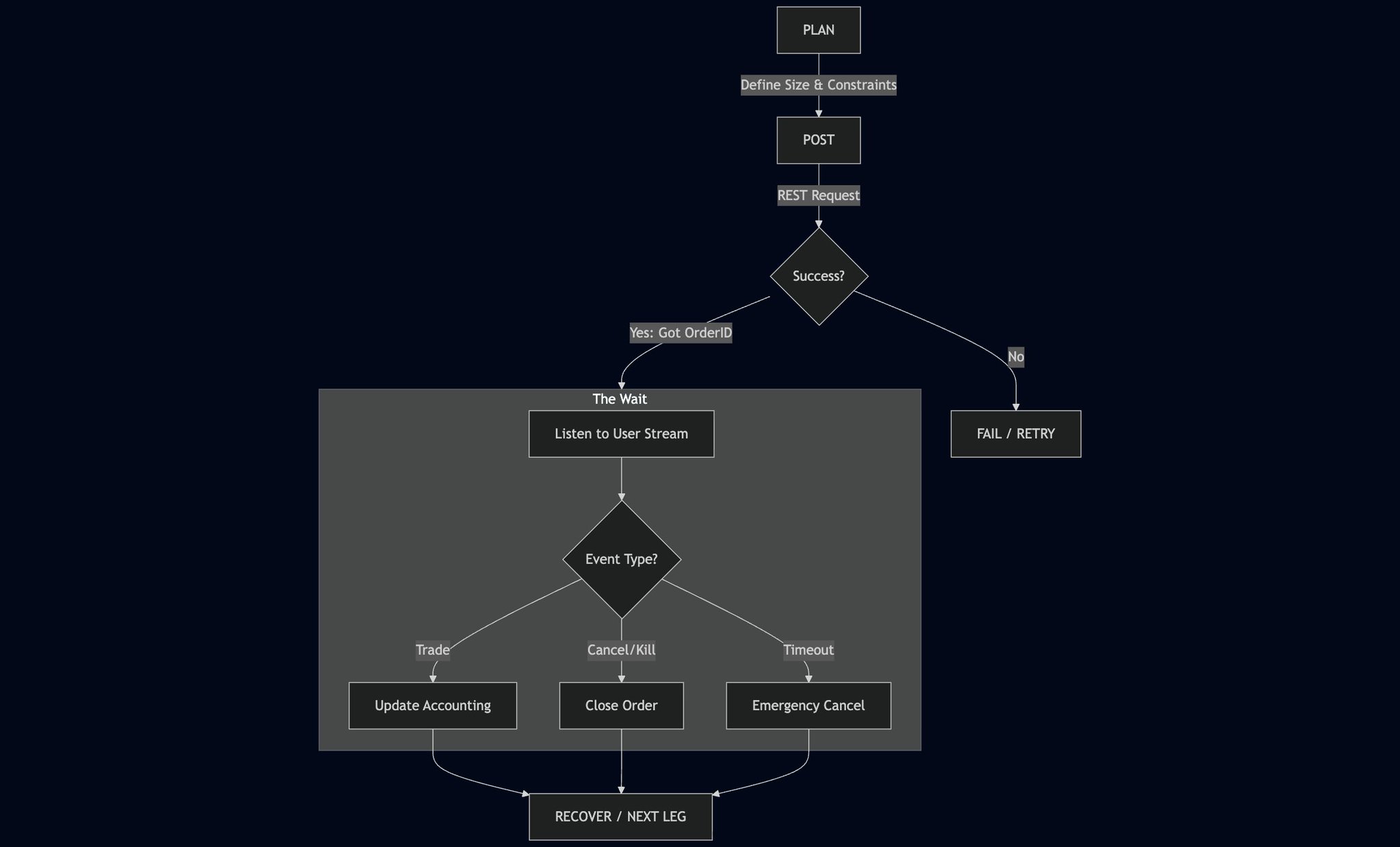

3. The Execution Loop

To prevent naked exposure, your execution logic must act as a state machine. It moves from planning to waiting, and finally to accounting.

Step A: Plan and Post

Before sending bytes, define your constraints. Is a partial fill acceptable? If you are arbitraging, the answer is usually No, so you force FOK. Send the order and capture the orderId from the response. If the API errors out immediately (e.g., "Insufficient Balance"), abort the loop.

Step B: The Wait (Confirmation)

Once the order is sent, your bot enters a blocked state. It waits for the User Stream to speak.

- Matched: You receive a MATCHED event. You now update your internal inventory.

- Killed: You receive a FAILED event. This means liquidity vanished before you could take it. The attempt failed, but you are safe (no exposure). In the case of FAK/FOK orders usually get rejected before (when being posted).

- Timeout: If 2 seconds pass with silence, you enter the Unknown State. You cannot simply assume failure. You must send a CANCEL request to force a terminal state before unlocking the bot.

The Execution Loop: A state machine that prevents phantom fills

4. The "Almost Filled" Trap

There is a specific production failure mode regarding "Market Buys" that requires defensive coding.

Because Market Buys are denominated in USDC (Dollars), floating-point math ensures you will rarely hit an exact integer share count.

The Scenario: You try to buy $100.00 of Trump=Yes.

The Math: At a price of 33.3 cents, the engine calculates you bought 29.998 shares.

The Bug: Your bot's logic waits for shares_filled == 30. It never happens. The bot hangs, times out, and assumes the trade failed—even though you actually own the shares.

The Fix:

For FOK/FAK orders, do not validate against an exact share target.

Listen for Terminal States.

If status is MATCHED or FAILED, the order is done. Record the reported size. Move on.

Floating-point math means you'll rarely get exact share counts

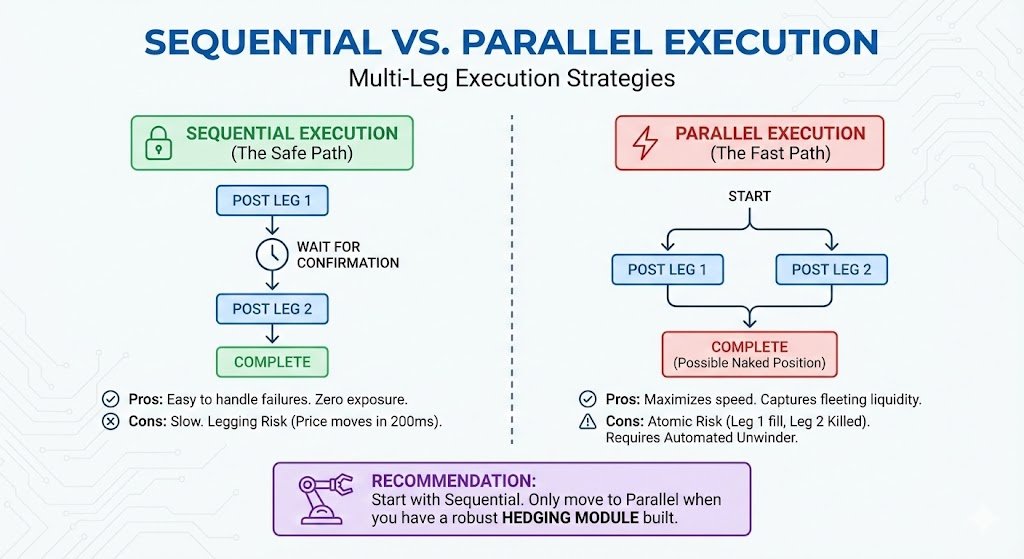

5. Sequential vs. Parallel Execution

Once you master single orders, you enter the world of Multi-Leg execution (NegRisk Arbs). You have two choices:

Sequential Execution (The Safe Path)

You post Leg 1, wait for confirmation, and only then post Leg 2.

Pros: It is easy to handle failures. If Leg 1 gets Killed, you simply stop. You have zero exposure.

Cons: It is slow. In the 200ms it takes to confirm Leg 1, the price of Leg 2 might move against you ("Legging Risk").

Parallel Execution (The Fast Path)

You post Leg 1 and Leg 2 simultaneously.

Pros: Maximizes speed and captures fleeting liquidity.

Cons: Atomic Risk. Leg 1 might fill while Leg 2 gets Killed. You are now holding a naked position in Leg 1 with no hedge. To do this safely, you need an automated Unwinder (which we will cover in Part 5).

Sequential vs Parallel: Speed vs Safety trade-offs

💡 Recommendation: Start with Sequential. Only move to Parallel when you have a robust hedging module built.

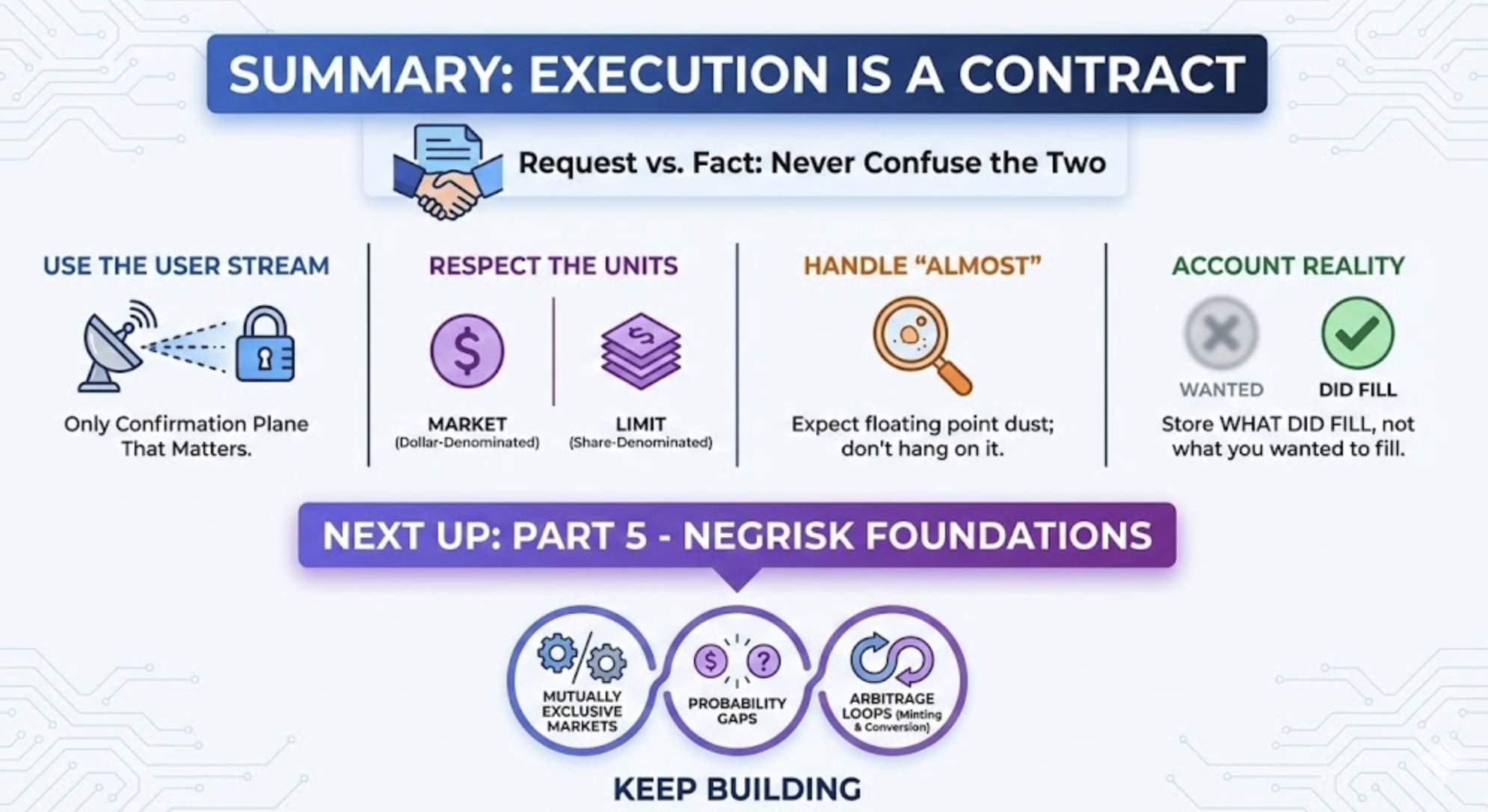

Summary: Execution is a Contract

Placing an order is a request. A fill is a fact. A production bot is built around the discipline of never confusing the two.

Key Takeaways:

- ✗ Don't trust HTTP responses — They only confirm receipt, not execution

- ✓ Use the User Stream — It is the only confirmation plane that matters

- ⚠️ Respect the Units — Remember that Market orders are dollar-denominated (with min/max shares), while limit orders are share-denominated (with min/max price)

- 🔧 Handle "Almost" — Expect floating point dust; don't hang on it

- 📊 Account Reality — Store what did fill, not what you wanted to fill

What's Next

We can now execute reliably. Next we analyze profitable market structures.

Part 5 covers NegRisk Foundations.

We will cover mutually exclusive markets. We will explore why fragmented books create "probability gaps." We will learn the specific arbitrage loops (Minting and Conversion) to profit from these inefficiencies.

Continue the Series

- Part 1 - Microstructure Before Math → Understanding venue constraints

- Part 2 - Selection is Performance Engineering → How to filter thousands of markets

- Part 3 - The Local Mirror → WebSockets & State Management

- Part 4 - Getting Filled → (this post)

- Part 5 - NegRisk Foundations → Mutually exclusive markets & arbitrage

- Part 6 - Strategy Implementation → Coming soon

Links

This article is Part 4 of the ZEIT Finance series on building Polymarket trading bots. ZEIT Finance turns prediction markets into perpetual assets.